There are a lot of parts to this story: the textile, how I found it, what it’s own (partially known) story is, what I decided to do with it, and the work and result of that. This may be a long post, but I think that’s better than dividing it up into episodes. I also hope the story continues, and will happily add updates when there’s more.

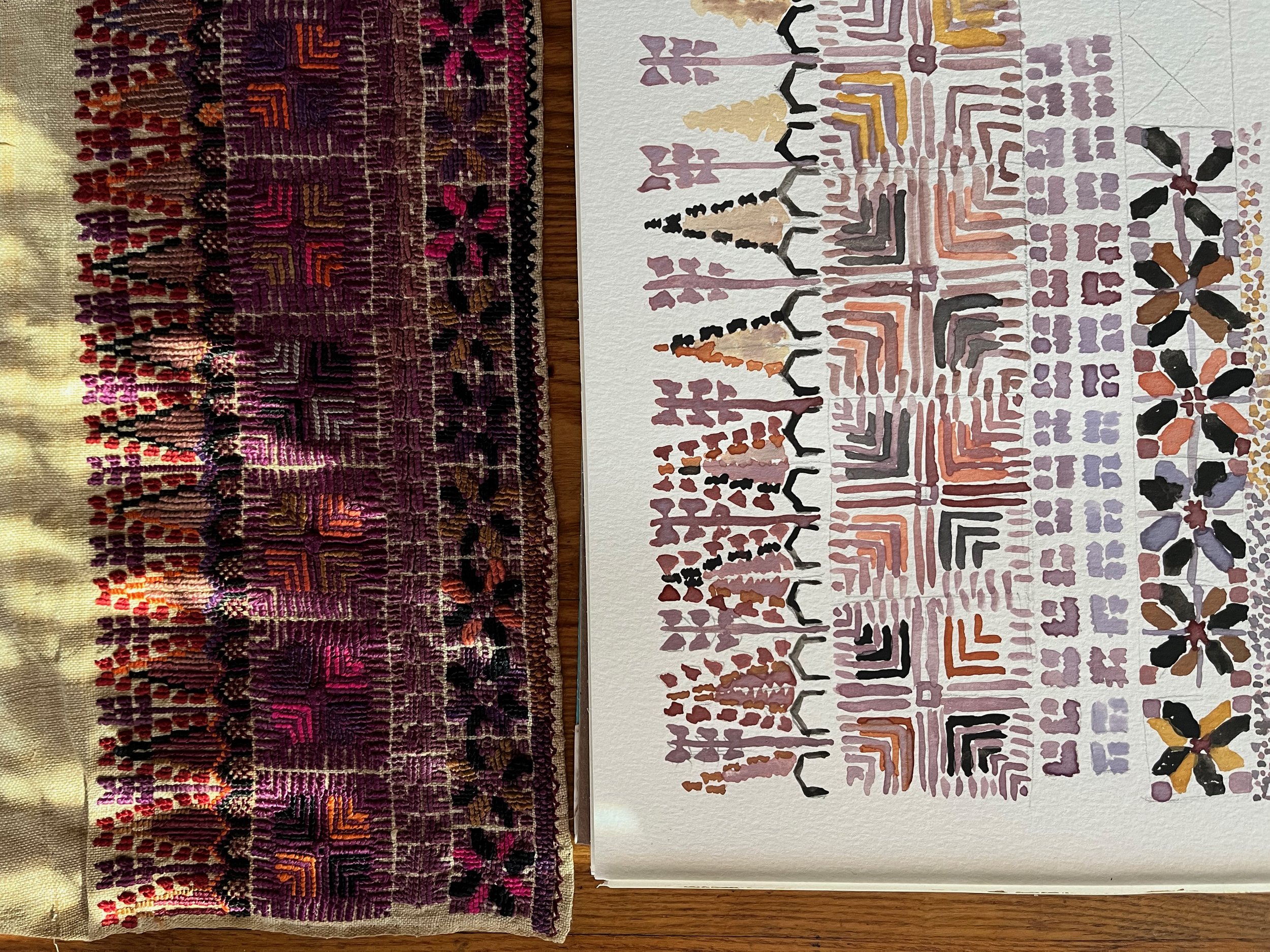

Tatreez piece, rolled up and prominent in my studio. For more information on tatreez: Tatreez and Tea, Tatreez Traditions, Tiraz Home for Arab Dress are all excellent resources.

Having found this piece in January, 2023, I will have lived with it for almost exactly one year. The uniqueness of a handmade piece makes it like a person’s face, something you learn to recognize beyond doubt. So the presence of it becomes familiar. I kept this piece visible in my studio for many months before I knew what I would do with it, and its face is precious to me. Even now, I sit and stare at the photos, enthralled, and have to urge myself to work with words… in some ways, the textile says everything on its own.

At the time of finding it, the attack on Gaza had been under way for (only) 3 months, and the sight of Palestinian embroidery pierced my heart. Somehow I felt that it was older, made as part of an original garment, but I didn’t really know anything for sure except “Palestinian cross stitch.” It was in a consignment shop in Port Townsend, Washington, where many of us buy and sell each other’s goods. It had been sewn by machine into a sturdy linen border & backing, which I left on while I contemplated what to do with this piece, apart from posting photos online over and over again.

When I finally removed the border linen and held the tatreez piece by itself for the first time, the voice of it came to life. Handling an old textile, there is a liveliness, a warmth to it, like holding someone’s hand. Being able to touch both sides and to see the back was like a direct communication with the maker, the woman who held it before - a more intimate listening to the language she wrote with her stitched marks.

Then I learned more about this piece. I noted that the three uniform-sized panels are not the style of design used for a Palestinian dress. Reading further into Shelagh Weir’s Palestinian Costume book, I saw that the Hebron area head shawls, or ghudfeh, have three panels, and bands of embroidery along one end. Using ghudfeh as a search term, I found other examples, also identified as Hebron works. Clicking through links, I suddenly found myself looking at exactly the same embroidery patterns, in a portion of a shawl in the collection of the Textile Research Centre of Leiden, Netherlands.

Doing a watercolor painting of a textile is a great way to study the designs, complexity, scale, and color choices, to learn more about the language.

The same! I knew the designs well, having looked closely enough to try to paint them. I still don’t know what this similarity means, exactly - what is the microcosm of shared embroidery vocabulary that would result in such an identical design… same family, or village, or time frame within an area? I haven’t successfully communicated with any textile scholars about this yet, but it’s certainly striking - I’ve looked at a lot of tatreez, and this is the only time I’m aware of seeing identical patterning. The benefit is that I can more confidently place the segment I have in time and place. And the conclusion of the TRC folks, in consultation with Wafa Gnaim, is that their piece is c.1900.

When we talk about old textiles, I know there’s a tendency to glorify age for its own sake - older pieces are more valuable, considered more authentic. Sometimes this is unfair to anyone still making textiles now, and in terms of the marketplace, I believe in supporting active craftspeople and not inflating value based on scarcity or exclusivity of access. (I’m also opposed to the way the textile collecting world mirrors the rest of the fine art luxury market in this way, with artificial fashion trends and status competition affecting the way things are valued. The inherent value of textiles and why they matter has nothing to do with all of that.) When I revere something older, it’s because of the life that is in it, the context that was woven or stitched into the piece itself, through materials and technique and the lived experience of the maker.

In this case, finding out how old this piece is likely to be was emotionally moving, because it places the original maker before so much of the suffering and disruption that her people are experiencing now. These stitches were made before Israel was established as a country, before anyone in this woman’s home environment was being forced to fight for their ability to live there, or flee. Her voice is grounded in place, and the language of her composition flows like confident music. Knowing that this piece was made in the pride and faith of belonging, of fully living her culture, makes it a powerful message from an ancestor, something to pass on strength and integrity of being.

Magnified view of the cross stitch embroidery - the white lines on the side are millimeters.

Which leads me to the obvious need to put it into Palestinian hands. I’d been contemplating this, how to give this on to someone for whom it would have personal, identifying meaning. And after meeting and beginning a correspondence with the musician Abdul-Wahab Kayyali, (whom I have mentioned before) the thought occurred to me: could it be made into a gift for either display in the home, or to wear? I had not yet come up with anything when he happened to mention in an email that he was interested in wearing tatreez while performing. This gave me a concrete goal, and I started thinking about a wearable base that could serve as support for this textile.

Abdul-Wahab Kayyali plays with guitarist Tariq Harb as the duo 17 Strings.

I envisioned a boxy jacket that could go over a dress shirt, with the tatreez wrapping around the jacket body, above the hem. I think I was influenced by Southeast Asian tribal clothing shapes in going for a black, square jacket - but I also found these Turkish fellows looking very sharp, which I was sure the recipient would appreciate, given his musical and personal Turkish connections. The Turkish image gave me the idea to use piping along the neck and front opening. I got some black linen twill from my local fabric shop, and found a suitable silk for piping in my stash of fabrics I’ve dyed in the past. After a few practice runs with making and sewing piping, I took the plunge and cut the linen, creating a piped edge along the round neck and center front, between two layers of linen.

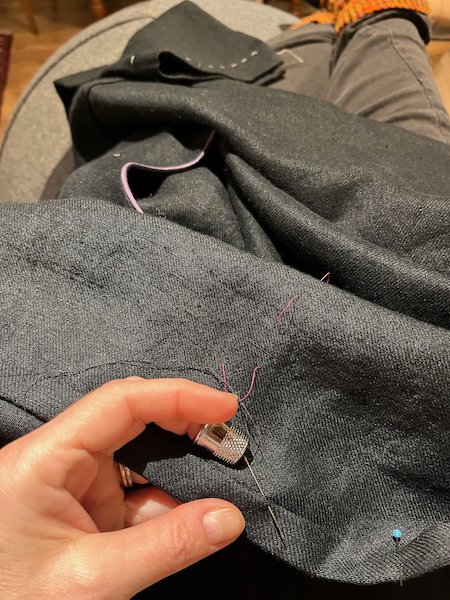

Piping is basted onto one side in the first step

Linen is shifty stuff, so there was much basting. The two layers of the jacket body were basted before cutting the neck, and here I’m basting them again after sewing the piping in the neck edge, before adding sleeves.

I decided on a T pattern with square gussets for the sleeves.

(I’m narrating it slightly out of order. I was already well into the project when I found out the age of the piece. This caused me to [hyperventilate and buzz around going omg and then] be more thorough in my documentation of the textile, especially the back which would no longer be accessible once it was mounted on the jacket. I will make the images and information available to others who work with preserving Palestinian textiles, if they are interested.)

Magnified view of stitches including joining stitch. Millimeters marked at the side.

The back side of the embroidery

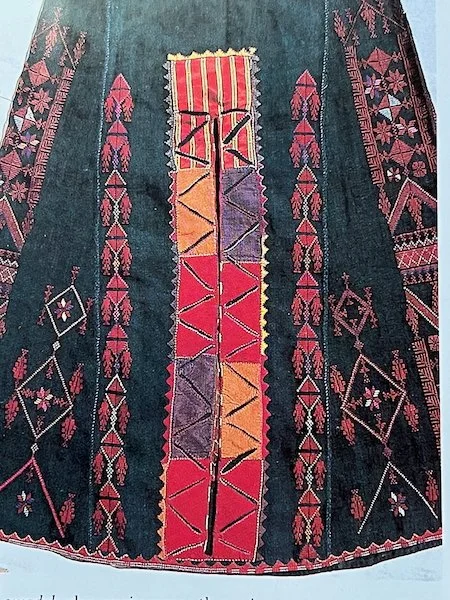

Given that the sleeves would be visible, I wanted to add something decorative on the cuffs. In dresses from the 1930’s or earlier, Palestinian women used imported silk taffeta to appliqué onto the skirt panels. A typical design is a rectangular strip with diagonal lines made by reverse appliqué. A slit is cut into the silk, and the edges are turned under and stitched. I knew this technique from other textile cultures, and had done it myself in the past. I auditioned a few different silks and practiced the reverse appliqué several times over, before working it onto the jacket sleeves. The cuffs have a small vent, and are hemmed with lines of running stitch in handspun yak/silk yarn. Running stitch is another embellishment that is seen in Palestinian garments and cloth.

Some of my reverse appliqué samples, with the preferred choice in the foreground.

Image from Shelagh Weir’s Palestinian Costume book showing a dress with taffeta appliqué in the center front of the skirt.

Spindle-spun yak/silk singles, sewn in rows of running stitch along the cuff hem.

The idea was to provide a supportive, wearable base for the tatreez, consistent with some aspects of Palestinian textile culture, while not drawing attention away from the embroidery. It is different enough from any traditional garment that, I hope, it takes the tatreez sufficiently out of context to be essentially honored as an element of traditional culture, and not co-opted in a way that conflicts with its original use.

Primarily, it is a way to connect the voice and art of an ancestor with the living continuation of her culture, to make it possible for others to continue listening to and learning from the beauty and message and strength of this textile. I hope that it will provide deep-rooted support for this musician as he expands his creative and expressive potential through composition and performance. Like the tatreez piece, his music is powerful, compelling, and tapped into strong cultural roots.

Abdul-Wahab Kayyali during a performance of Mafaza, in a screenshot from the Instagram of Majd Sukar, co-composer of the Henna Platform production. Photo by Joshua Best.

The image above was concurrent with my beginning work on this jacket, and I hope I can convey how much it broke my heart. Mafaza is a powerful stage production, involving two Syrian poets, Waeel Saad al-Din and Mosab Alnomire, and two musicians, Abdul-Wahab Kayyali and Syrian clarinet player Majd Sukar. The debut performances were in early November, 2024 in Toronto. I was compelled by the trailers and interviews that Henna Platform was sharing as the performance date approached, and I knew from Abdul-Wahab that creating this work was a strong experience for all of them. What I didn’t know until I saw this image was that the musicians, who were on stage the whole time along with the poets, were dressed and made up as survivors of an explosion, with torn and dirty jackets and dirt-smeared faces. The fact that they performed the whole time in the garb of the bombed, embodying the dehumanizing, targeted status that many would give them, was almost too much to fathom. And the contrast between this and the type of jacket I’m trying to make, the message I’m conveying with it, that this musician is esteemed and worthy of the best, most meticulous efforts - it still squeezes my heart when I think about it.

When I describe the details of the textile and the garment making, I’m trying to be thorough with the information, so I get into report-writing mode. But the feelings are there in the work and care, and the truth is I often had difficulty working on this project and not crying. It feels like the most important thing I’ve done in recent months, and one of the most significant textile projects I’ve ever had the honor to work on.

Beginning to stitch the sleeve detail, while listening to Les Arrivants.

Sewing the hem on Dec 7, 2024, the night that Syria was being liberated.

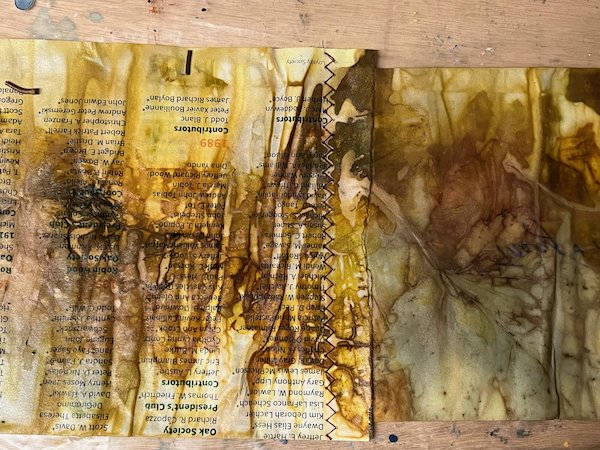

After the sleeves, and after sewing the hem, the only thing that remained was to attach the textile. I had one of those sudden bright ideas that come while lying in bed, regarding the stitching for securing the textile. Given that the jacket has two layers, if I quilted them together with colorful sashiko-type stitching, I could conceivably stitch the tatreez onto the top layer only, and then the stitches wouldn’t show on the inside of the garment. I basted guidelines for the top and bottom edge of the tatreez placement, and did some decorative stitching in between with (cotton) embroidery floss. (see finished photos)

The tatreez textile is tacked to the jacket body, which is wrapped around a large pillow.

Securing the textile along the top. The tricky part was sewing through the top layer only. The curved needles helped.

For mounting the textile, I needed a support that would hold the body of the jacket in a rounded way. I used a large throw pillow, covered with cotton cloth, and laid the jacket onto the textile, then wrapped it around to the front. After securing in several places with stitching rather than pins, I began to sew along the top edge, with white linen that was darkened with natural dye to match the old linen cloth. This was a chance to bring out the textile conservation needles - tiny little curved needles that are nearly impossible to thread and hold, but that make minimal holes in the textile. After a few minutes, I got back into the habit of holding the wee needle, and this part of the work was calm, reverent, and rewarding. Every moment of looking closely at this piece has been a gift.

Finishing the stitching on winter solstice, with the setting sun lighting up the tatreez textures.

Detail of finished jacket: bound side seam in foreground, interior decorative quilting stitches, and the outside of the jacket in the background, showing piping and textile.

When I finally hung and stepped back from the finished jacket, I was overwhelmed by a mix of emotions and anticipation, barely able to wait for my visit to Montreal and the giving of it.

As it happened, I was visiting Abdul-Wahab Kayyali on the 19th of January, 2025 - the day the ceasefire went into effect in Gaza, so the wild mix of emotions continued, and how could it not? The heaviness of all the surrounding story, of historical and present-day suffering, are bound up in this textile, this garment, and the friendship that has caused me to make it. Even where there is joy, and beauty, and love, deep pain is an inherent texture of it all. It brings Rilke’s phrase from a letter to mind: “Wie sollen wir es nicht schwer haben?” How can it not be heavy for us?

Nevertheless, it makes me very happy to report that the fit is just right, it works well with playing the oud, and when he first put it on he said, “Perfect.”

I’m quite sure there will be more photos of this project, here and there, and I look forward to sharing its public debut when Abdul-Wahab Kayyali chooses to wear it for a performance with Les Arrivants.