Knitters will be familiar with the phrase “at the same time,” which indicates that while you are knitting a section according to the pattern, you also have to keep in mind an incremental increase or decrease every few rows. (In my case, this phrase almost always indicates that I’m going to lose track at some point. Holding multiple sets of instructions with staggered moments of crucial attention is not my forte, especially since I like to knit while reading or watching a program.)

In the context of this post, the phrase has a more sinister and dangerous meaning, because it refers to the multiple contradictions we are required to hold, or at least parry and dodge, or simply observe in disbelief, if we are trying to pay attention at all to our world.

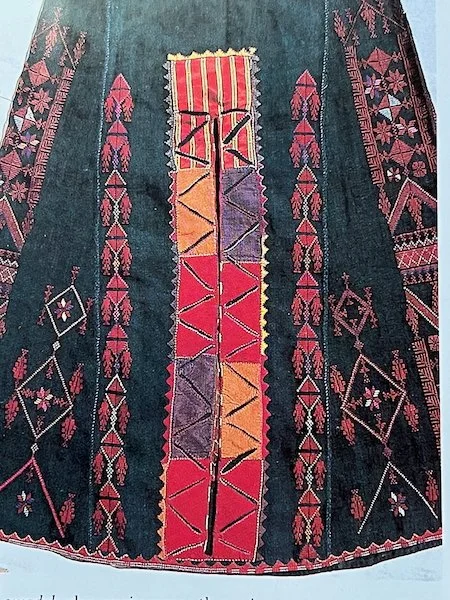

Detail of the skirt panel of a tatreez dress I bought in Aswan, Egypt in 1994

I came across this video on YouTube, with the description posted below: Tatreez exhibits at the Victoria & Albert

“This video is made to coincide with the exhibition 'Thread Memory: Embroidery from Palestine' at V&A Dundee which runs until Spring 2026, and the 'Tatreez: Palestinian Embroidery' display at V&A South Kensington until May 2026, curated by Jameel Curator Rachel Dedman. The exhibition and display are free to visit.”

The curator’s video tour of the textiles does not mention the Nakba, or contextualize the garments in historical and political timelines, merely admiring and narrating their material characteristics and mentioning their origins in location (gratifyingly repeating ‘Palestine’ many times.) At first I suspected that it was a timely gesture toward uplifting the beauty of a ‘lost culture’, with objects decontextualized in a manner similar to that described by Wafa Ghnaim in her essay for the Met last year. However, the exhibit itself does not avoid or gloss over historical and factual information, as is evident from its iteration in Saudi Arabia, and also from the resources page of the current exhibit in Dundee.

It is the V&A’s first collaboration with the Palestinian Museum, and there seems to be a sincere effort at respectful education and honest highlighting of Palestinian culture and history. Notably, comments on the video are disabled, which is atypical for V&A’s YouTube channel, and The Guardian decided to print a letter to the editor calling for increased ‘plurality’ in the exhibit’s representation of Palestinian culture, complaining that Christian and Jewish Palestinians were not included (not linking to that one). That’s a small "at the same time”: the fact that highlighting of Palestine predictably elicits a complaint that Jewish voices are being ignored.

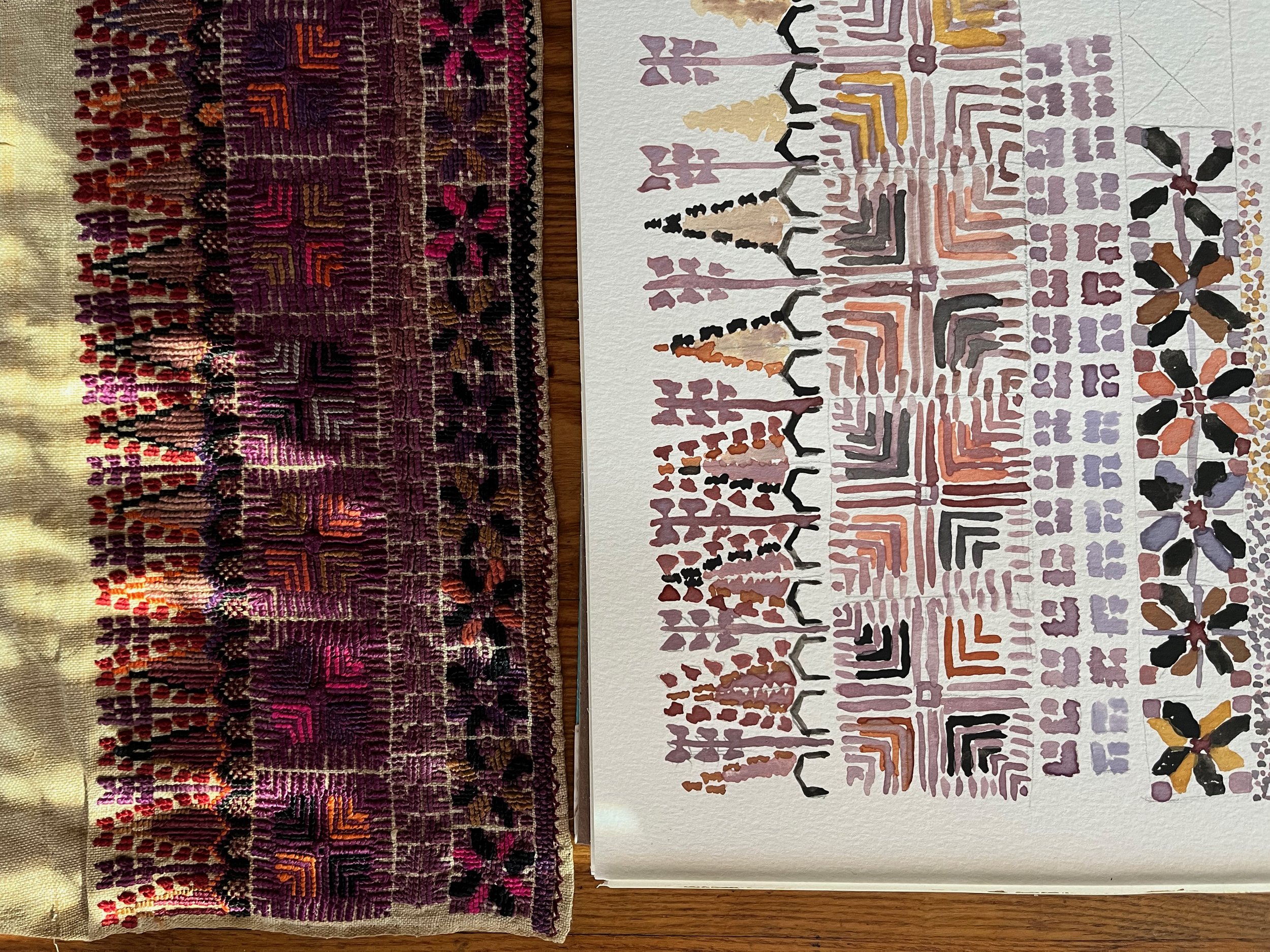

Shoulder detail from the tatreez dress I bought in Aswan.

At the same time on a larger scale, dozens of people are being arrested for showing support for Palestine Action in the UK. The organization has been proscribed as a terrorist group because some people vandalized military equipment with paint. Read that sentence again. This designation causes the UK government to feel justified in devoting resources and police effort to arresting large numbers of demonstrators of all ages, even if they only sit with a sign saying “I support Palestine Action.” I’m having a hard time holding the museum exhibition and the police action in London simultaneously in my mind as the stance of a coherent state, and it’s only the very tip of the mass of crystallized contradictions, most of which have much more dire consequences than museum exhibitions or protest arrests.

Grafitti in Bergen, Norway

Some days later: I wanted to say more, the so-called ‘news’ keeps barreling ahead, with no palpable change in trajectory, and we continue to be required to hold multiple contradictions in mind, just in order to live. The confusion of all this is helpfully addressed, to some extent, in this William Shoki article on attention as freedom, and the corrosion of cognitive ability by the digital information realm. He begins by talking about how the genocide in Gaza carries on and yet becomes less real to the global public, then analyzes this process incisively, saying:

“This is not simply a media problem. It is a crisis of subjectivity. A slow unravelling of our ability to perceive clearly, feel coherently, or act collectively in a world saturated by images, algorithms, and engineered doubt. This disorientation is not incidental to moments like this, but is their background condition. What we are seeing is not only a political struggle over Gaza and how it is understood, but a deeper transformation in how reality itself is mediated and experienced.”

It’s a long article, and I recommend reading the whole thing, with many thanks to Josiane who sent it to me. As someone who is committed to studying how the mind works, I take this analysis very seriously, and seek to protect my own and others’ independence of thought and freedom of learning. Rebecca Solnit’s latest newsletter addresses this as well, noting the human meeting ground that books provide, a humanity that cannot be replaced by technological stunts. My favorite part of this newsletter might be the images of books. They give a comfort and reassurance, as my own bookshelves do, that there is a record of deep human experience and thought which is accessible and present, wise people who can be listened to at any moment.

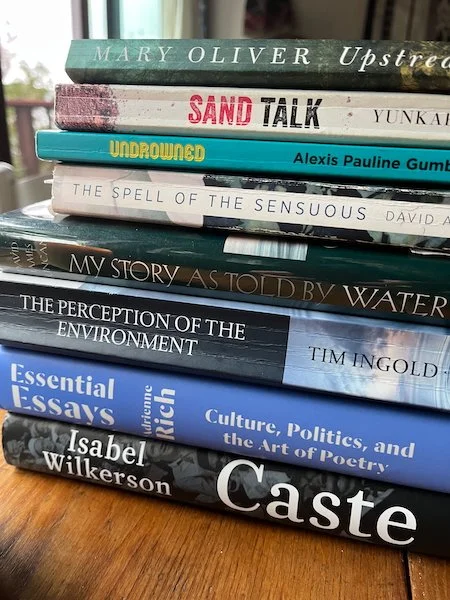

A small selection from the nearest shelves.

I’m also reading the poetry of Fady Joudah and Andrea Gibson, a recent and scintillating Rumi translation by Haleh Liza Gafori, and expanding my Rilke world with the Mark S. Burrows translation of the Sonnets to Orpheus. Without losing sight of what is happening, without pausing my ability to feel and continue to speak about Palestine, I find ways to tend my mind and heart that will not disable or dissipate, but strengthen the base of care.

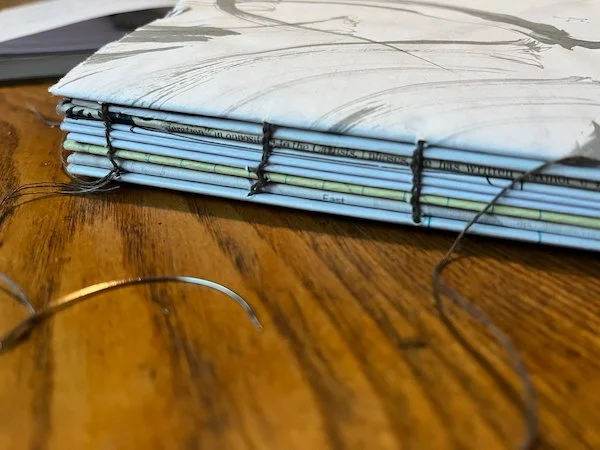

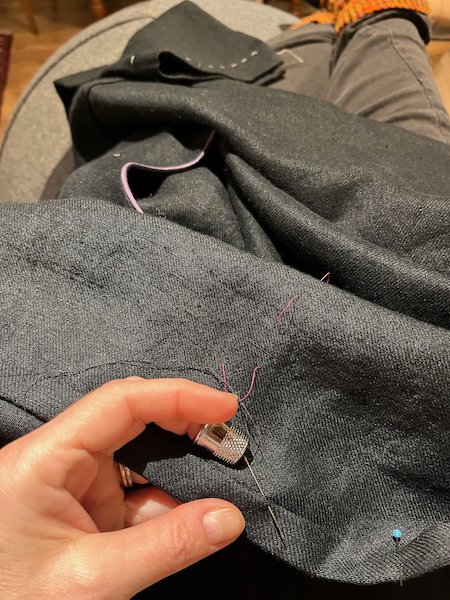

Stitching a sketchbook from repurposed papers - a small and practical pleasure

On the ground, in the face of the deliberate starvation of those in Gaza, World Central Kitchen is doing their utmost to provide meals, and so is Gaza Soup Kitchen.