I know, it’s hard. It’s hard because we live in a world overcome by industry, which has taken many of us far away - the more industrialized, the further - from hands-on knowledge of how cloth and complex textiles are made. I don’t actually expect most people to understand terminology such as ‘warp-faced complementary warp pickup,’ or even ‘backstrap loom,’ but I still make note of it when showing my work, to specify the technique I used.

It’s similar to indicating whether a two-dimensional work on paper is a lithograph, an etching, a charcoal sketch, a monoprint, or a watercolor. These are all ways of making the thing, and it’s directly relevant to the artist and how they work. A watercolor painter won’t necessarily be able to create work using etching or printing techniques, and the work wouldn’t look the same if they did. The techniques are fundamentally different, and the art is expressed through the chosen medium, all of a piece.

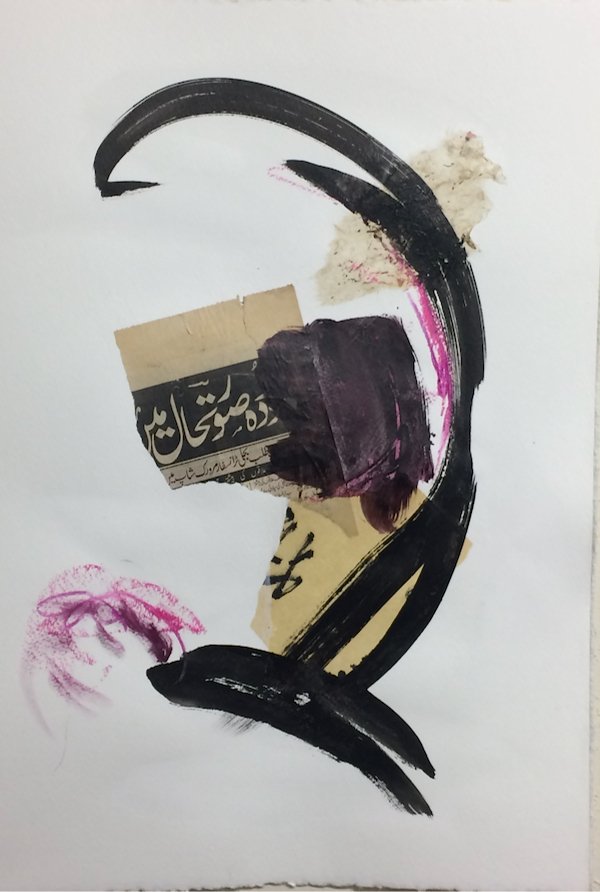

mixed media, 2018 - sumi ink, acrylic, pastel and collage on paper

Likewise, when someone is a weaver, there’s a surprisingly wide range of techniques available, even if the medium is always tensioned yarn of some kind. The language available to us modern-day English speakers is limited and distorted by our lack of experience with making cloth. “Tapestry,” for example, is a mis-used word, perhaps most famously in reference to the Bayeux Tapestry, which is in fact an embroidered cloth. In common English usage, the word tapestry tends to refer to a textile that is hung on the wall, regardless of the technique used to make it.

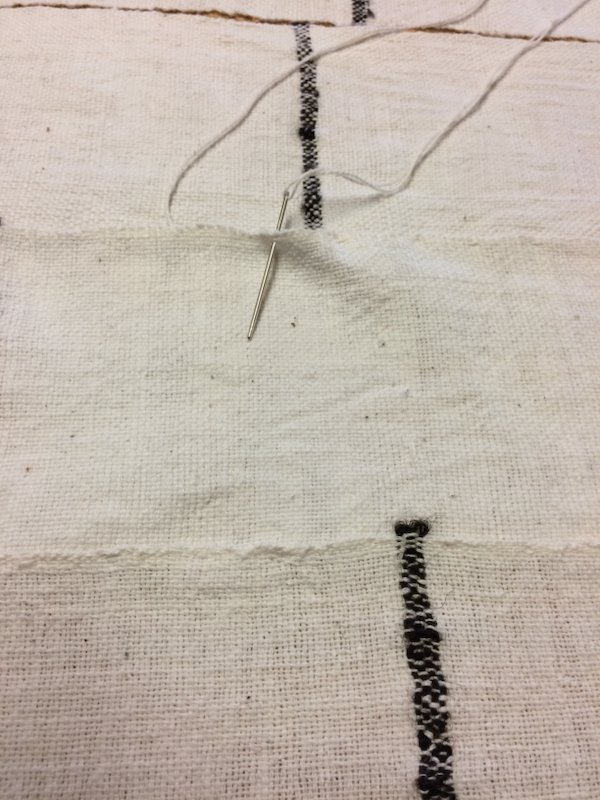

plain weave strips of handspun cotton with wool stripes, being stitched together

Tapestry as a technique is exemplified by historical European wall coverings like the famous unicorn tapestries, by ‘flat-weave’ rugs such as Turkish kilim, and by artists such as Sarah Swett, Rebecca Mezoff, and Mary Zicafoose. Tapestry weaving is weft-faced, meaning the yarns you see are the weft yarns, covering the tensioned warp completely. Traditional Navajo rugs are also woven in this way, each row of weft yarn packed down tightly against the previous row, to form a smooth field of color. Contemporary artists of course muddy the waters for the layperson - for example Sarah Swett also indulges in backstrap-woven balanced plain weave, and Mary Zicafoose’s website offers hand-knotted carpets based on her tapestry weavings, produced in a workshop in Nepal. But the techniques are in every case noted alongside the textiles, so that you are never being misled by the artist. Textile artists tend to expend some effort (as I’m doing now) to explain how their work is made. This is not often expected of other artists, and I think we do it because our love makes us want to help people appreciate what’s going on with this stuff. That’s essentially the purpose of this website, to elucidate a few things about textiles.

more warp-faced complementary warp pickup, ‘loraypo’ pattern, using handspun wool

My work with the backstrap or body-tensioned loom - fundamentally some sticks and a belt around my body - tends toward the warp-faced, because this is what naturally happens when a warp is tensioned with the body: all the warp yarns crowd together closely. Traditional Andean designs take advantage of this, and use the warp yarns for patterning. Complementary warp pickup alternates warp yarn colors within a pair such that whatever is not up is down, and the pattern on the back of the weaving is the exact opposite of the front.

Bedouin style weaving in three panels, with supplementary warp patterning, made from handspun Navajo churro sheep’s wool

Another way to created warp-faced patterning is called supplementary warp, because an extra warp yarn is included, so that in each row you can choose which color to hold on top. The center pattern section of the weaving above, known as shajarah or sāhah in Arabia, has both dark and light warp yarns in each warp. The color that is not held to the front floats on the back.

weft float design based on Central Asian yurt band, using handspun wool

Okay one more, if you’re with me…. this is a warp float pattern commonly used among nomads of Central Asia and Iran. The warps are paired in two colors as with the Andean weaving, but in this case the pattern yarns are raised above everything, skipping or ‘floating’ over a row. The reverse side does not mirror the front in this case, but just looks like alternating stripes.

Bear in mind that each of these styles of patterning represents a different logic, a distinct way of thinking and of forming patterns. This effects what designs are possible within that logic, and it creates a kind of language and/or mathematics in the mind of the weavers who use these methods from a young age - their way of understanding is informed by their approach to weaving. This is where weaving becomes cosmic and mind-boggling for me.

plain weave black wool in progress

The other thing I do is plain weave. It has been a goal for some time to be able to weave balanced plain weave cloth, aka tabby, the basic over-under pattern that underlies what weaving fundamentally is, and create usable fabric, with my backstrap loom. I’ve written about this often, and have probably shared more images of work in progress than anyone needs to see, but there’s something enthralling about this view, the weaver’s perspective on the warp as it becomes cloth.

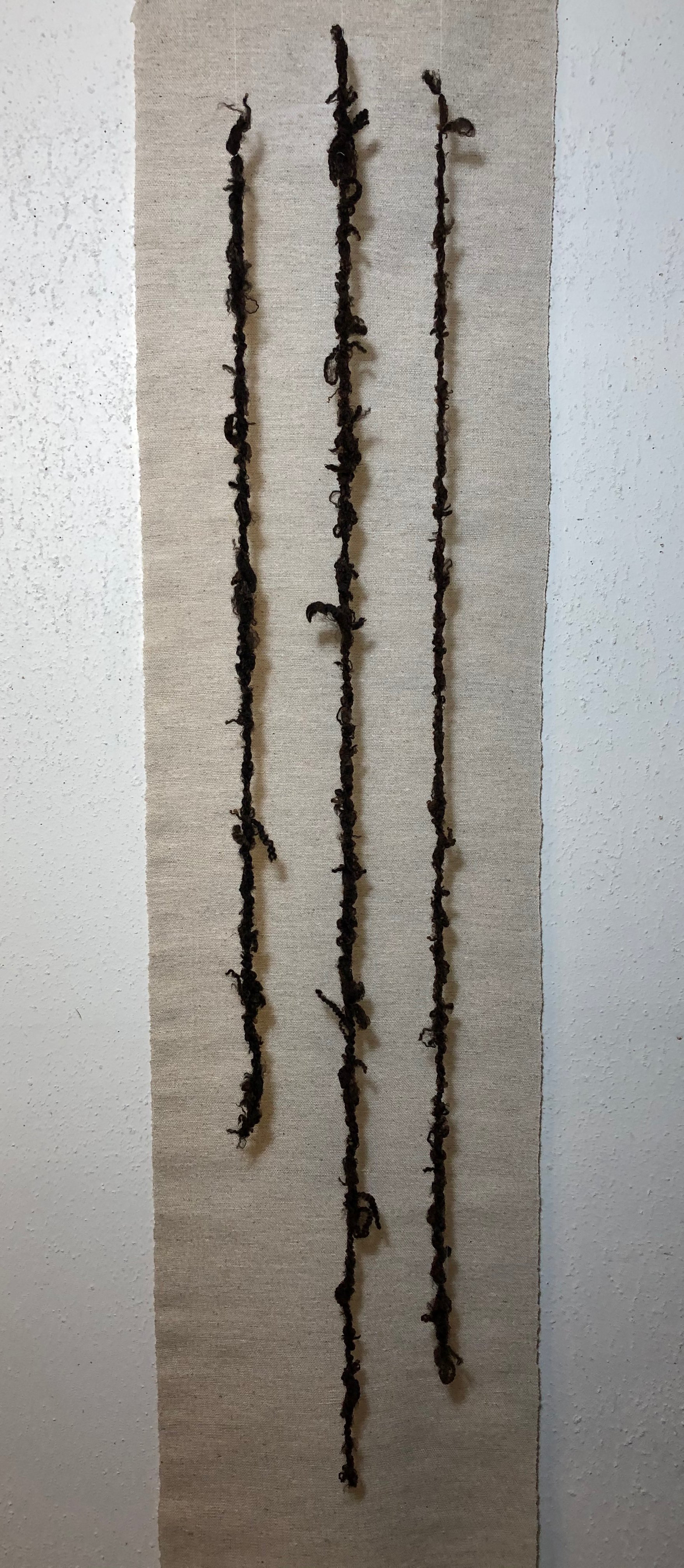

In order to really get warp and weft equally visible and ‘balanced’, I need to use a reed to hold the warp yarns in place. When I learned to make a bamboo reed from Bryan Whitehead in 2017 (two links because there were two posts about it,) this became a possibility for me, and I’ve been honing it ever since. Most of the cloth woven for my show earlier this year was plain weave, hung as ground behind lines of handspun yarn.

In hopes that this is more entertaining than pedantic, I’ve written this in order to elucidate some of the specifics of the weaver’s medium, and where my own work falls within the vast spectrum of weaving possibilities.

handwoven linen/cotton ground, handspun lambswool lines